“There’s your ride.” Dr. Trish pointed from the balcony of Hotel Kakanyero toward the large, white, off-road vehicle. The vehicle was the standard Non-Governmental Organization issue, noticeable from afar and newer than the few vehicles seen around Gulu Town.

Gray clouds were slowly rolling in, and dust from the dirt road flew as boda bodas, a sort of motorbike taxi, sprinted past. “Hi Ketty. We need to get a few things, then we’ll be right back.”

Ketty is a Team Leader with the Justice and Reconciliation Project’s (JRP) Gender Justice Program; she works intimately with formerly abducted women who’ve escaped from the Bush, often with children that will suffer social stigmatization. Today she was going to take us into the field with her to talk to local, rural women and give them the donations we’d collected for their community.

“From up?” Ketty questioned.

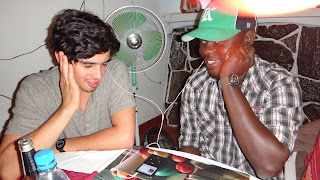

Hilary, a fellow GSSAP student chimed in, “Yes, and get Dr. Hackett.” Moments later, with four bags brimming with clothing, school supplies, and balls, Hilary, Adrianne, Dr. Hackett and myself piled into the SUV. I was tucked into the posterior compartment where four seats faced each other, two on each side. Donations were heaped on the seats across from me and next to me while a quiet, young woman sat in the remaining seat. Patrick, another team member of JRP who was driving, moved to secure our door, “Apwoyo (ah-foy-o), my name is Patrick,” he said with a smile as he reached out a hand. I took it firmly, returning his grin, “Apwoyo, Jaymelee, but they call me Lakisa Jane.” Unlike the soft-spoken Ugandans, I had replied loudly, to ensure I was heard over the busy street. His face lit up even more, “ah Lakisa,” he repeated before moving to take the wheel to begin our journey.

My backseat partner was Sarah, whom we later learned was one of Joseph Kony’s many wives. After escaping with some of her children from the Bush on foot, she began volunteering and working with other women who had been forcibly taken as LRA wives. She remained quiet.

Between Ketty’s warm conversation and stunning scenery the forty-five minute ride passed quickly. Rolling grasslands, spattered with fields of corn or beans, continued as far as the eye could see. Tall palm trees rose like sentinels stationed throughout the countryside, and in the distance beautiful hills marked fertile hunting grounds. Cool air snaked through the open windows as we were jostled along the bumpy, eroded, red-dirt roads. Most travel on the path was done via footing (walking), bicycle, or boda boda. Countless women walked, often carrying babies secured to their backs by blankets knotted tightly across their chests. With items carefully balanced on their heads, sometimes padded by a coiled scarf, they transported logs, jerry cans, and produce. In addition to them, we passed heavily loaded bicycles that frequently featured a man pedaling with a woman sitting on the rack holding a child or other goods. In a similar fashion, motorbikes bounced along, often with multiple passengers and significant baggage.

The smell of licorice and chocolate filled the air, depending on which sweets were being passed around the vehicle, and gray clouds grew darker before we finally pulled into the district headquarters. Along with the rest of our group, I was bustled into the District Chief’s Office (an appointed position), and I was surprised by the state of things.

Appearing new, the cream-colored building stood in staggering contrast to a small cluster of round houses, or huts, that stood to its west, and a gray, dismal health center that neighbored to the east. Similarly, the office walls were brightly painted, and nice furniture filled the room. To follow was a bit of pomp and circumstance as we were asked to sit and introduce ourselves. As our group leader, Ketty explained the purpose of our visit and asked if we might use the community hall to hold a meeting with the women of the area. After some expected politicking and displays of power assertion that occurs when one is the visitor, the Chief said only half-jokingly that perhaps our group could donate money to him, to make his office nicer with more computers. The sad irony is that often in these rural communities computers are not even considered an option because they do not have any source of power to operate them, nor the education.

Unfortunately our experience with him is not an uncommon encounter in areas overwhelmed with NGO presence. A culture of dependency in post-conflict reconstruction becomes the established norm, and both individuals and communities begin to assume that outsiders only exist to provide monetary support. Rather than working toward empowerment and self-improvement, people begin to think within the confines of a welfare state; people forget that “teaching a man to fish” is even an option.

We were led to a sizable, empty hall, filled with plastic lawn chairs and flooded with natural light from the windows that lined the walls. Slowly women trickled in, and after about fifteen people arrived, we started the meeting. While I had expected only a meet-and-greet of the briefest nature, we experienced much more.

After some difficulty in explaining that we were there not as sponsors, but as students, the group began to share some of the challenges they face in their day-to-day lives. In accordance with various reports read and lectures heard, women explained that they faced several primary and cyclical problems in this new time of “peace”:

- Abducted at a young age, they had limited education, and could not read or write.

- They returned with children from the Bush, whom new husbands refused to support.

- In order for their children to receive an education, the mothers had to support them.

- The mothers had to support them with limited educations and no vocational skill training.

In order to begin tackling their problems surrounding economic livelihood, the women had begun a community microfinancing project. Essentially, every week, individuals pool their money which can then be lent out to group members with an interest rate of 10%. Ideally these funds would be used as capital for launching new businesses; regrettably, they could not pool enough money to create a sustainable business.

Moreover, their new, non-LRA husbands often were drunkards, or had other wives and children to support, creating competition for resources within one family. Their circumstances were stymied by a lack of resources and a largely unsupportive male community. Was there someone in the community who could tutor others in reading and writing for a small fee? Could women band together in communities in lieu of increasing their burdens through marriage? Why hadn’t NGO’s sent teachers or vocational skill trainers instead of erecting new administrative buildings? Could the work that JRP is doing partner with my internship organization (War Affected Children Association) since it is trying to address similar problems of sustainable livelihoods?

We also asked the ladies for their opinions on the appropriate mechanisms for justice and community healing. The responses were insightful and honest as rain pummeled the roof of the town hall. The more I heard them talk, these women who escaped the LRA, some who escaped the hands of Joseph Kony himself, the more I believed that the primary question should not be, as many lecturers suggested, of creating sustainable peace, but rather of creating sustainable change. Clearly when given opportunity and tools these women can succeed, or else they would not have been in that meeting hall today.

As the adage teaches us, they do not need more fish, they need to learn how to fish and have the tools to do so.