I do not want to play down the profound significance of the lectures we heard for one week at the Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies at Gulu University from an impressive array of war survivors, peace-builders, religious leaders, community workers, and humanitarian, human rights, and development experts. Nor would I wish to diminish the richness of the students’ internship experiences in their various host institutions in Gulu Town, whether the local hospital, arts center, government office, education or development NGO, interreligious, sports, or cultural organization. Nor would it be right to underestimate the impact of our excursions into local communities in the region to learn how they were trying to recover from the effects of war and eke out a living for their families.

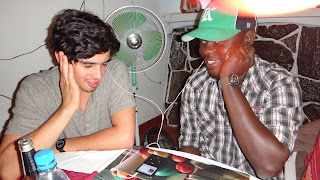

But it was also under the roof of our downtown hotel, Hotel Kakanyero, that lives were being transformed. Through the friendships that our students forged with the staff in the hotel--whether they worked in the restaurant, the reception, or the laundry--the hotel became a home. Life stories were shared, jokes were exchanged, and before long, when the day’s work was done, there were social outings to local coffee shops, restaurants, and Internet cafés. The young people even joined forces at a popular quiz and social night at a nearby hostelry to constitute the Hotel Kakanyero team! These human interactions, occasioned by a building, reminded me of that wonderful novel about a Cairo apartment building, The Yacoubian Building, by Alaa Al Aswany.

But it was not all about sociality. Our GSSAP students had learned enough from their new friends about their hardships as well as their hopes. They knew that some of them had been abducted and served as child soldiers during the war, that some were war orphans, that others had unpaid medical bills, and that several could not afford to complete their schooling. In next to no time, the students had raised money to purchase shoes, backpacks, and a bicycle, and donated funds to help start a poultry project, pay school fees and medical bills for at least four of the staff. There was also help with email addresses and Facebook accounts, and gifts of clothes and even beloved IPods. The significance of the Mark Twain quote, posted at the TAKS Art Centre that we frequented, “the best way to cheer yourself up is to try to cheer somebody else up” was really driven home.

On the final day of departure, there were hugs, tears, and endless photo opportunities. The students were moved by the gifts they received in turn from their Ugandan friends. But it was the letter was pushed into my hand from one of the waiters (with apologies for the spelling) that arguably had the greatest effect: “Your students could make me smile the whole day and night in the course of my duties. I will never have such friends again till they come back to Uganda.” Indeed we will, thanks to GSSAP.